The hive of discussion on how to improve the Irish League is always abuzz.

Whether on or off the pitch, the spoken, overarching ambition of organisation CEO Gerard Lawlor is to see greater professionalism throughout the NI Football League.

Earlier in the season, the former Cliftonville chairman unveiled the league body’s five-year plan titled ‘A Bold & Brighter Future For Professional Football’ which, of course, had that professional ethos to the fore.

That includes NIFL’s own in-house media, covering the Premiership, Championship and Premier Intermediate League as well as the BetMcLean Cup, as well as the clubs’ own coverage to beam out a product on the rise. Inherent emotional attachments are commonplace in football and the custodians at clubs are expected to be standard-bearers for a modern, progressive landscape.

After all, it is important to clarify that full-time football – again, a target of Lawlor’s that he has affirmed on more than one occasion – is not the only way to instil those values. It is not the be-all and end-all.

Larne, Linfield and Glentoran have each adopted fully professional models, Crusaders employ a three-quarter full-time strategy while Cliftonville are drafting in a hybrid set-up with Jim Magilton their first full-time boss, but the overwhelming majority of clubs throughout the three tiers of the Irish League remain part-time institutions.

That’s why any alterations to enhance professionalism are done with consultation from the teams involved, and the current talking point within the domestic football sphere right now is the reintroduction of the salary cap.

While there is not universal agreement on bringing back the cap, which had been abolished during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the proposal has proved popular with many sides – although it may look different this time around compared to the last wage cap, which was introduced back in 2011.

Outside investment has allowed Larne and Glentoran to go full-time; the Inver Reds were taken over in 2017 by home town businessman Kenny Bruce and the Glens were bought by Ali Pour in 2019.

Larne, somewhat languishing in the Championship when Bruce came onto on the scene, have totally reinvented themselves in the six and a half years since; after a rampant run to the second-tier title in 2019, they have clinched a three-peat of County Antrim Shields, are in the Final of a fourth and continue to toast their magnum opus – a first-ever Premiership crown in 2023.

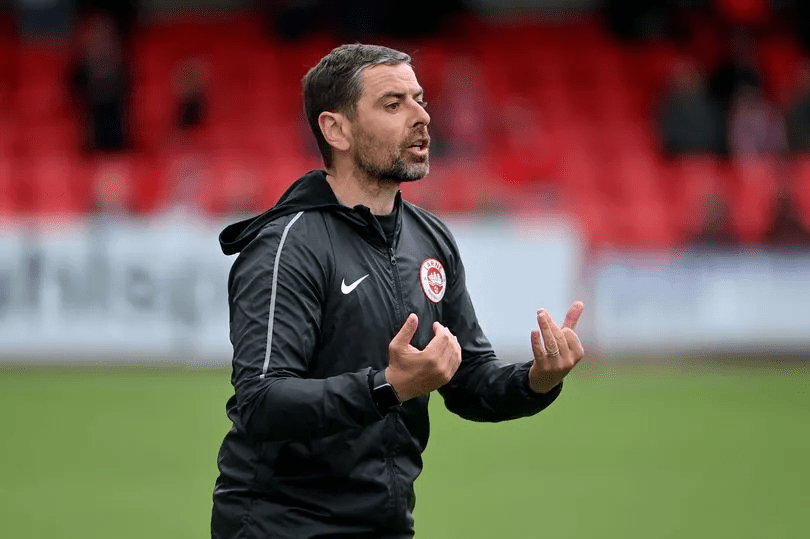

Under Tiernan Lynch’s tutelage for every single step of the way, the east Antrim establishment who celebrate 135 years of existence in 2024 have scaled new heights. Playing Champions League football was a daydream in a not-too-distant past; let alone that, last summer, they took HJK Helsinki, the long-standing Finnish titans, all the way to extra-time.

The basis on which their success was built is a sustainable and structured model that is ruthlessly efficient. Bruce, by his own admission, has invested £5m and more to make it happen, but the rewards have paid dividends.

That is the potential of investment – and it can co-exist with a salary cap. It was in place both when Larne were first taken over and when they won the Championship with 81 points from the 96 available.

But with investment must come regulation. That is where the onus falls on clubs and governing bodies to make sure frameworks are in place for a so-called ‘boom and bust’ scenario is averted.

The 12 Premiership clubs met this week to mull over some of the hottest topics in the domestic game right now – and, although no agreement was reached, the cap was high on the agenda.

Larne boss Lynch has voiced opposition to it as recently as the previous week when he told the Belfast Telegraph: “It doesn’t make sense to me. I think Northern Ireland football has a huge amount to offer and we are only scratching the surface of what this League can achieve and where it can go.

“We have four European places and I think rather than imposing a cap, we shouldn’t be limiting ourselves.

“I think we should be looking for investment throughout the league and for all the clubs to go full-time.

“We need to maximise what we have which is an excellent game with good players, coaches and managers. We need more recognition and TV deals.

“I think we sell ourselves short a little bit at times. There’s a mentality we are just Northern Ireland and we’ve been a part-time league in the past.

“We need to smash through that mentality and be proud of what we have and believe we can be even better.”

You can see the point he is making and, yes, as in any league, clubs should be collaborating to do what is best in the interests of all.

At the same time, not every club has access to a full-time set-up – though in the last six months, Carrick Rangers have welcomed American executive Michael Smith on board as majority shareholder while Coleraine and Bangor have also entered talks with potential investors having both had financial difficulties in the past.

As explained, a majority of clubs are part-time, and fully professionalising the league isn’t a process that can happen with the flick of a finger.

Nor can it be rushed into.

One point often raised is, indeed, the topic of inflated wages itself.

Combine this with a top-six, bottom-six split that has emerged within the top-tier of late and, without regulation, we could see a scenario where those within the lower half may invest more than their means allow to keep up with the pacesetters.

That would be dangerous – and it’s exactly what a wage cap could prevent.

Coleraine have faltered in 2023/24, which has seen the gap to sixth-place slashed as newly-promoted Loughgall (one point behind), Carrick (two) and Glenavon (three) have stayed hot on the Bannsiders’ heels, but over 20 points split sixth and seventh come the split last year.

A cap on player wages, however it is determined, may close this gap and perhaps eradicate it entirely.

Like anything, that will also take time. Patience is a virtue, and in the last five years alone, there has been much change in the climate of the Irish League.

However, the signs point to a pragmatic approach to professionalism on the part of those in charge.

If we want to see a full-time division come into effect, these frameworks are wholly necessary; sustainability, coming through baby steps like these, is a must before moving onto some of the bigger questions.

Would investment be stunted by limits on the wage structure?

Well, if Bruce and Pour weren’t deterred by it when the cap was in place first time around, you’d like to think the appeal wouldn’t be lost on those eyeing up such opportunities.

The Irish League remains an attractive product, and you can notice a trickle-down effect in the lower tiers, too.

The Championship is an entertaining, end-to-end frenzy where teams are out both to win and please, while the PIL is enhanced in quality and as competitive at the top end as it’s been in some time.

Talent-wise, the diaspora is growing throughout the divisions. Investors would be putting their money where their mouth is.

The domestic scene is in a good place and there is an ecosystem in place that allows players to flourish at all levels. It would not be healthy, however, when we are at a stage where we know who will finish where in the Premiership before a ball has been kicked.

A salary cap – done correctly – can protect clubs and ensure the competitive edge is retained, while not limiting investment opportunities or restricting player growth.

Bringing it back would not hamper the NI Football League but rather can help take it to a new high.

Featured image from Pacemaker.

Leave a comment